Subtle Horror

- S. Yumi Yamamoto

- Oct 24, 2018

- 6 min read

In 2008, at the age of 18, I sat through my first real horror movie: "The Orphanage". It is one of the only movies I've seen where the horrible happenings has a truly happy ending, but that didn't keep me from screaming so loudly I woke up my friend's parents in the middle of the night. I was terrified of my dorm shower for weeks, and I still don't like little old ladies walking across the street. While I had seen movies like "The Grudge" before, I hadn't really watched the whole thing because I was far too scared. I know I'm late to the horror party, but that scarring is exactly why I avoided it. All the cheesey jump scares and troupey supernatural horror still scared me up until I decided to take control of my fear to understand the story. That particular story: "Five Nights at Freddy's".

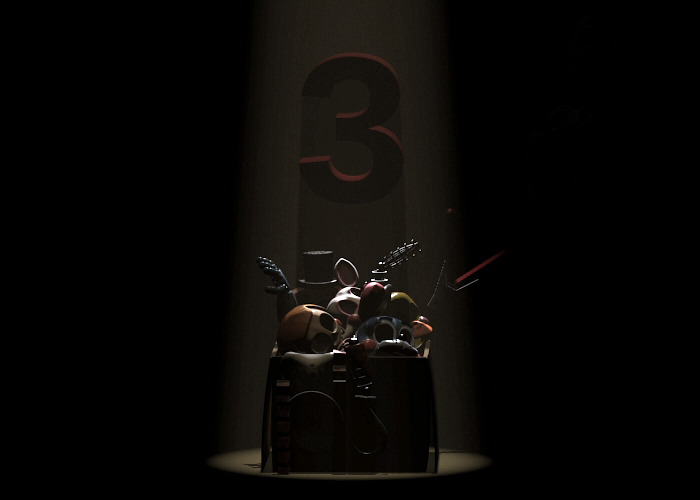

For those of you know aren't into the indie gaming scene, "Five Nights at Freddy's" was released in 2014 and was a "new take" on horror games. Instead of walking through an environment, escaping or shooting up everything in sight, you are confined to a single room the entire game. It's five (or six) levels where your character is night security guard at a Chucky Cheese-type establishment with animatronics that roam the restaurant at night. They, uh, want to kill anyone in a security guard uniform, so you have to survive by closing doors, looking at creepy robots through the sketchy surveillance cameras, and also NOT running out of power before your shift is up. As you can guess, it gets progressively more difficult as the levels progress, and one of the animatronics doesn't follow conventional rules. The mysterious Golden Freddy sort of just pops in and out, giving you haunted jump scares that disrupt your concentration and scare the ever-living f*** out of you. This game has several sequels, all of which play on the same trapped-in-a-room, omg-I'm-running-out-of-power, why-is-that-robot-looking-at-me kind of scare. The environments are creepy, the games are difficult, and the story is almost not there if you're not paying attention. If you want more info about just HOW subtle and complicated this very simple-looking game is, watch the GameTheory videos on YouTube... FYI, this is several hours of content, but totally worth it in my opinion because MatPat is the closest to a complete, accurate theory according to the creator Scott Cawthon. Also, it's all highly entertaining <3

But that's the interesting thing about FNAF: the main game is full of jump scares (some of which are rather cheap), but the story is subtle. We learn more about the story as the games go on. While the mini-games are more direct storytelling vehicles, even then we aren't given all the pieces. People on the internet have debated for YEARS about what the timeline looks like, who the characters are, how they all connect (if they even do), and just how many dead children there are in these games! It doesn't detract from the game, either. If anything, going through the theories makes the game better! It's the unsettling origination story that makes the characters even more frightening, but only if you take the time to understand them.

That's what I love about the subtle types of horror: the "ahah!" moment mixed in with the terrifying realization that everything you figured out until now is about to kill you. Sometimes it's the slow, creeping sense of unease that culminates into the terrifying truth. Other times it's a mystery where the horrifying events start to make sense to the point where, if you were in that position, you might have made the same choices. This isn't survival or escape, and it's not good versus evil. Subtle horror forces the protagonist to face and deal with the issue without pushing morality. In fact, the characters' decisions should make them feel uneasy, even try to justify their actions in a convoluted way. That makes stories like 'Frankenstein' timeless. The horrifying issue isn't about bringing dead flesh to life, or the monster killing people; it's about facing death and loneliness, fatherhood, and the choices that the characters make in order to handle their losses.

I was writing horror before I really understood what it was, but I knew what I liked. Gore-porn or slasher horror wasn't my style, and supernatural horror only went so far for me. People are more terrifying than anything (though when the house shifts in the middle of the night when I'm alone still gives me the heebee-geebees). I just wanted normal people put in a situation in which they adapt in the most dreadful way possible. But, this isn't Poe's "Telltale Heart" which is fear, guilt, and regret eating away at the protagonist. It's the Donner party, stuck and starving in the snow, debating whether or not to eat their fallen friend to survive. Honestly, I think that's why I like when horror deals with cannibalism/grotesque foods so much. We know it's wrong for a number of reasons, but when it happens it's usually a conscious choice. That choice to eat or not to eat, and following up with the description of emotions and taste, is something that disgusts and engrosses me. It handles a change in a person, focusing on a decision to make rather than a situation to survive, and that (to me) is more timeless and powerful than a haunted house.

Now, this type of horror doesn't make for a good movie or TV show, and it definitely doesn't make for a good novel. At some point we need dramatic action to break up the time. Subtle horror is best left to the short stories/novellas and short films of the world. It's why FNAF is mostly a jump-scare game with a subtle story in the background. If the story was at the forefront of the game, we'd get bored very quickly. It's also why the games are short, even though there are so many of them. (While I acknowledge the existence of two, incredibly long novels that belong to the FNAF franchise... let's just say that neither of them got rave reviews.) Subtlety in horror requires a lot of set up, but also requires the story to quickly get off of the moment to make it last. Dwelling too long on the situation can cause the audience to desensitize themselves, and thus it stops terrifying them.

To take games as an example again, horror games will have a set cast of enemies that vary in difficulty. This is to be expected of any game, but horror can (and should) withhold certain enemies. There are some enemies which are designed to be scary - whether that be their sound, movement, abilities, or strength - but if you face them too often the player will start to figure out its weaknesses to the point of total domination. For example, the main monster in 'Amnesia: the Dark Descent' shows up so rarely that his very sound sparks fear. Yet, when you play enough mods (new stories/levels created by other players) the monster starts to feel lack-luster to the point of not being a threat. On the same note, it's the reason why the "water monster" of these games still work (and have traumatized me forever); water levels are few and far between in the mods and in the game, and so when a player suddenly approaches a flooded environment, the invisible thing that hears your splashing still frightens them.

(Skip to 9:21)

Taking this to a literary level, it's difficult to sustain the looming threat of a cast of monsters/threats because at some point the reader will desensitize themselves or get bored. Horror novels must portray a different kind of horror in order to keep the reader interested and invested in what's happening. In a short story, there isn't enough time to show the threat more than a handful of times, and the story is able to play with seeing, sensing, and feeling the threats, or doubting that it's there at all. Thus, short stories have a wider range of horror. For subtle horror, the reveal/last point of action ends up being the last part of the story, with barely any falling action/denouement at all. The reader is there for the feeling of terror or horror, and that feeling must stay with them if the story is to have an impact.

What's your favorite kind of horror? Or do you hate the genre? Let me know

Comments